I was asked to contribute recently to a paper on aspects of horticulture, mainly because I still retain a decent library of old tomes and modern ones on the subject.

This is a small part of that cut and pasted from the whole, and re-arranged for putting up on here.

Whilst the fact that the Romans planted vines with varying degrees of success even in the north and did make wine is taken for granted, we have little or no knowledge of what that wine would have been or the vines used. Naturally they would have been imported, and they certainly imported wine as amphora discovered in large amounts testifies to that fact, so the actual amount that was made here could have been quite small. However there is evidence of some vine planting with the discovery at sites of grape seeds and stalks, and aerial surveys show vineyards in the Nene Valley area that were for wine production.

The fossilised remains of Vinus vinifera sub sylvestris have been found growing in the Hoxnian period, an interglacial time when it was again warmer than today, though this was some 400,000 years ago when mainland Britain was still joined to continental Europe. It is the second sub species Vitis Vinifera sub vinifera that is the base for all the cultivated vines, some 8-10,000 up till today.

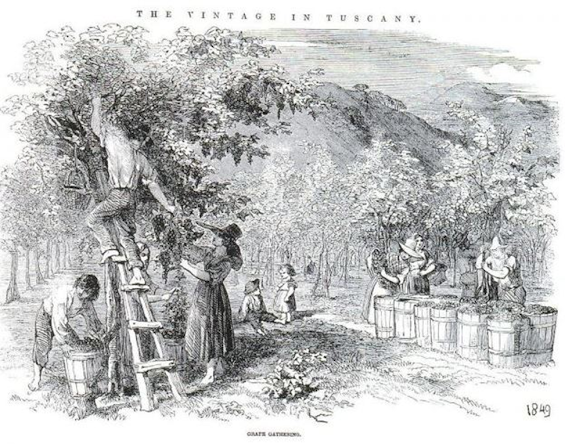

Of interest re the Romans is that they introduced the Elm to Britain or the Atinian clone of it, sadly now all but wiped out. Why did they import a tree species? It is believed they used it to grow vines on, a method widely used then and even into the 19th century.

One aspect that crops up over the time since the Romans planted vines is the climate that has been through several phases of hot and cold periods. The time span for each has been variable such as the big freeze in 1963 when we had three months of snow; in past times the Thames would freeze and frost fairs were held on the ice, especially between the early 17th and early 19th centuries when we were in what is now known as the Little Ice Age.

Most frost fairs were held on the upper reaches where the tide was least likely to interfere with the freezing, but the removal of the old multi-pier London Bridge helped the tidal flow and further finished the freezing effect as we came out of the Little Ice Age. This is one of the many indicators as to weather over the centuries that affected the way we lived.

We also had warm periods during this time and before: the Roman period of 2000 years ago was warmer than now and very warm between 21 and 50AD and continued and tapered to around 300AD, so it is not surprising they grew grapes and made wine here.

The medieval warm period lasted even longer, from circa 950AD to 1250 AD. Despite no continuing Roman influence it is surprising to find that the Doomsday book records around 40 + vineyards in the south of the country, so somehow the growing of vines and the knowledge of how to had been retained. Or was it? Details of these vineyards is scarce as the Doomsday book is not exactly proficient with detail.

This period falls within the time of Norman Conquest and the expertise of the monks in wine-making and the monasteries that made wine is all well recorded. The Conquest also coincided with the warm period so wine-making was not a difficult task for the experts from France.

It would be nice to think that some vineyards had survived since Roman times until the second warm period, but it is highly unlikely that any grape growing was going on after the Romans left; what was left behind would have soon been lost without their expertise.

The second warm period also came in very quickly at a time of no industry, so man-made climate change can be ruled out of that one.

Records at Evesham, a monastic establishment in the twelfth century, show that five servants of the monastic staff were employed in the vineyard. In the thirteenth century the Archbishopric of Canterbury was supplied by just two vineyards at Northfleet and Teynham in Kent; Teynham was considered to be the parent of all fruit orchards in the land.

However, over time increasing trade with Europe and especially France and Spain made making our own wine became a lost cause and it diminished, finally disappearing after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536; besides, the ending of the warm period put paid to the practical side of grape production.

Not entirely though, there are always exceptions to the rule: Tudor times saw the first real interest in gardens and gardening after the Renaissance fed its cultural changes into all of Europe. Everyone wanted to be part of this movement and early horticulture was part of it.

It has to be said that early Tudor times saw little merit in the design or construction of gardens and gardeners were hardly recorded in logs of the time and had little status in the general employment of the time. Yet one entry during the reign of Henry V111 does show that a certain Lovell was retained to supply the King's table with ‘damsons, grapes, filberts, peaches, apples and other fruits, and flowers, roses and other sweet waters’; it is as far as can be ascertained the only mention of gardening, which consisted of food production as the main component, at that time. It wasn’t until late Tudor times that gardening took on any importance.

Again documents show that there were over 130 vineyards in the country when Henry came to the throne. Nearly all would have been in monastic hands and we all know what happened to them

The building of Hatfield House in 1607 is recorded in many detailed documents still existing. The enormous undertaking of the renovation by Robert Cecil the Earl of Salisbury of the old episcopal palace which the King had persuaded Cecil to exchange for his then property Theobalds, included large garden works and it included a vineyard. 30,000 French vines, varieties not recorded, were presented to the Cecils by the wife of the French minister, Mme de la Boderie.

We really have to jump to Jacobean times to start to see references to grapes in a broader sense. A well-known correspondent of the time John Chamberlain who partook in ‘week ending’ country house visiting, mentions visiting, not for the first time, Ware Park in Hertfordshire in 1619, where he speaks of the “ the best and the fairest melons and grapes”; this was after a long dry summer. And again at Lord Savage's house at Long Melford, Suffolk, where the mention of actual wine production is recorded: “ here you have your Bon Christian pear and Bergamot to perfection, your Muscadell grapes in full plenty, that there are some bottles of wine sent each year to the king.”

By the mid-1600s in the reign of Charles 11 gardening had become more mainstream and much improved and the influence of the French in growing choice fruits was permeating across the Channel. Sir Ralph Verny at Claydon in Buckinghamshire after a trip to France spoke of the abundance and quality of the fruit and vegetables, he himself had planted “good eating grapes of several sorts.”

Alexander Pope had a property on the Thames between Hampton Court and the London Road; there is a detailed drawing of the layout and it shows a vineyard within the grounds.

The mention of grape growing is scarce to say the least until market gardening to supply the increasing population of London gets mentioned in the 1700s. By the middle of that century London ‘kitchen gardeners’ or market gardeners today had become highly skilled in the art of fruit production. Fertile Thames side districts such as Westminster, Fulham and Chelsea are mentioned and it is assumed that this skill was being employed elsewhere. The use of hot beds, cloches and inter-row cropping was yielding produce all year round and it is amazing to think we were exporting to the Continent. The range of fruit for instance was astounding for the time: in cultivation during this period were forty-five types of pear, twenty-eight plum, twenty-three apple, fifteen of peaches!, fourteen of cherries, twelve different grapes, seven of apricots, five nectarines and three figs. Some private gardeners offered more: one Rev Hanbury of south Leicestershire offered for sale nearly forty types of vine among his other fruits, quite an astounding range.

This expertise was further advanced during the next century when a seven mile stretch along the north bank of the Thames was all market gardens. They further advanced the stretching of the seasons not by using glass but by building south-facing embankments to grow less hardy produce out of season; it is suggested that this technique was copied from the pictures and accounts of steeply sloping continental vineyards - there is no documented proof of this but by then knowledge of the methods would have spread widely.

Of course it is not easy to tell what and how much of the vine growing resulted in actual wine but one nursery does record the fact. It was called the Vineyard and was a walled area at Hammersmith; it was producing wine in the 1600s under the title ‘Burgundy wine’ though there is no evidence it continued the early seventeen hundreds. The site is now under the Olympia exhibition centre, and again there are no surviving documents of the type of grape being used.

Several of the new rich and landed gentry of the 18th and 19th centuries had vineyards as part of the new 'lanskip', all part of having the most and the best of plants design, and doable by the sheer wealth of the landowners. Most of these vineyards did not survive.

So we come to modern times. Not until after the Second World War was there an effort to research the type of grape needed to produce wine in this climate.

Ray Barrington Brock was a research chemist who set up a private research agenda to find the most suitable grapes to grow in England. His mistake was to assume that the hybrid crosses that the Germans had produced to combat colder climes were the answer; sadly it transpired they were not. Yes they grew, but they produced insipid wines in this land: who today goes looking for Seyval-Blanc, Muller Thurgau, Huxelrebe, Ortega etc? The thinking was that as they were early ripening that would solve the climate issues, but what was forgotten, or ignored, was that these varieties were not really intended for anything other than the bulk white wine trade in bad vintages or for blending in poor harvest conditions; most of these varieties are in decline in their homeland and now here, but it set the ball rolling.

So from between the two world wars when apart from a few hobby vineyards there was not one in commercial activity, we have moved to a period of growth with 700 vineyards of all sizes recorded across the UK.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)