An anonymous comment on the

preceding post has set me speculating further. The commentator says:

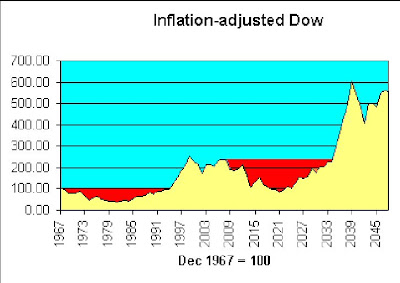

You are right, but I believe that this time around it will be equities, rather than commodities or real estate that will provide the hedge against coming inflation. Tobin's Q will prevail due to the juxtaposition of equity prices vs. the other two asset classes (which already had their surges) and the market's increasing valuation sophistication compared to the last time we saw hyperinflation in developed economies (i.e. the 1970s). So I've been buying stocks as an inflation hedge, despite the statistical evidence that this is foolish...Wikipedia offers an explanation of Tobin's Q

here. Essentially, Q is a measure of the relationship between the value of all a company's shares, and the value of the company's assets. If Q is greater than 1, there is some reason (real or imaginary) why the company has extra value to offer; if less than 1, a share investor could buy a company's underlying assets at a discount.

In 2006, Michael Alexander wrote a series of articles for Safe Haven, about stock cycles. Below, from the

second in the series, is his graph for Q in several bear markets, including the one which he suggests began in 2000:

According to this, Q was already below 1 in 2006, and since the market is now back to about where it was a couple of years ago, that would suggest that shares are now fairly valued in relation to company assets.

But if history repeats itself, the current bear market has a long way to go, since the other three lasted 15 - 20 years. And in each of the previous cycles, Q slumped below 0.4.

Another complicating factor, thanks to the lending boom, is the real estate bubble. Steve Moyer is firmly of the opinion that real estate is very heavily overvalued, even now. So a collapse in that market would push Tobin's Q back up for many companies, a technical indication that share prices would have to drop steeply to get back to fair value (let alone overshoot to below Q=0.5).

In this context, it's worth noting that one of Mike Alexander's books, published in 2000, is titled "Stock Cycles: Why stocks won't beat money markets over the next twenty years".

It's the volatility that does you in. As Keynes said, "In the long run..."

It's the volatility that does you in. As Keynes said, "In the long run..."