Sunday, June 29, 2008

Inflation not purely a monetary phenomenon

I looked at the Bank of England's figures for M4 from end 1963 to end 2007, and by my calculation the monetary base has increased by a factor of about 240; yet prices have increased only 15 times in the same period. (*)

Currently (and time permitting) I'm also working through David Hackett Fischer's "The Great Wave". In his concluding chapter, he lists seven different causal explanations of inflation, and none of them quite fits the observed facts, not even monetarism. For example, in the sixteenth century, European prices began to rise some time before the imports of gold and silver from the New World could have made a difference.

His idea is that inflation-waves are "autogenous" (don't academics love this kind of label?), by which he means that people make decisions based on current circumstances and their personal predictions for the future, and that helps shape the next set of circumstances. It's like watching a football game unfold, each player adjusting his movements according to his perception of the others.

Fischer thinks that one important factor in the price-wave of the Middle Ages was a trend towards marrying earlier and having more children, which put pressure on natural resources at the same time as altering the ratio of working adults to dependant children. Perhaps this has modern echoes in the growing longevity and reducing mortality rate in the developing world, plus the increasing numbers of dependant elderly in most places.

At any rate, inflation in the West is likely to become less susceptible to control by adjusting the interest rate. What will the Monetary Policy Committee do then?

Perhaps it might help if we established some control over the actual amounts pumped into the economy by the banks (and other creditors). I can dimly remember the news in the 60s, about limits on how much you could borrow to buy fridges, washing machines etc - apparently a minimum deposit was a requirement of the Hire Purchase Act 1964.

However (it seems), Japanese manufacturers found ways to get round this and offer (in effect) 100% loans, and then came the pandemic of credit cards, starting with "your flexible friend" Access (1972). Telegram Sam the drug dealer is always friendly, at first.

________________

(*) Unless, of course, the discrepancy is accounted for by (a) the need for the monetary base to expand each year to cover interest on loans already made, and (b) much extra money being locked-up in real estate - an awful lot of building and rebuilding took place as the postwar economy recovered.

Investment, inflation and market collapses

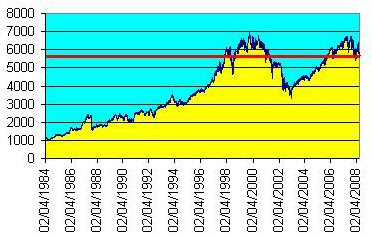

If you're an active investor, you may start thinking about opportunities. Look at the red zones. Draw a line from a deep points to a high one, and feel the greed; but draw lines from a temporary rally to another low, and feel the disappointment. You do need to get your timing right.

If you're an active investor, you may start thinking about opportunities. Look at the red zones. Draw a line from a deep points to a high one, and feel the greed; but draw lines from a temporary rally to another low, and feel the disappointment. You do need to get your timing right.Crime and punishment

Henry Wallis: "The Stone Breaker" (1857)

Henry Wallis: "The Stone Breaker" (1857)In a country with proper justice, nobody would dare intimidate a witness.

In such a country, wrongdoers are afraid of the law. They'd know that such a crime would certainly be prosecuted and that they'd end up doing at least 15 years breaking rocks.

... says Peter Hitchens in today's Sunday Grumbler.

"Pitee renneth sone in gentil herte," said Chaucer, sometimes ironically. The worthy compassion shown to unfortunates by the Victorians has, gone too far, some argue.

But there are now different reasons to pity. Prisons do not punish the wrongdoer in the old-fashioned ways, but the incarcerated man is no longer protected against bullying, beating, buggery and theft. In how many movies do we hear the police threaten a criminal with what his fellows will do to him in prison? Judge Mental does not put on his black cap and say, "You will be taken from here to a place of detention where you will have your arm forced up your back and..."

Then there's life outside, for the neglected underclass. "Theodore Dalrymple", a doctor who has dealt with many prisoners in Birmingham (UK), used to note in the Spectator magazine that prisoners' health improved considerably in prison, because of no (or reduced) access to drugs. Read the good doctor here on how the liberal approach to mind-altering substances is pretty much a sentence of death (prolonged and degrading). Here's an extract on alcohol:

I once worked as a doctor on a British government aid project to Africa. We were building a road through remote African bush. The contract stipulated that the construction company could import, free of all taxes, alcoholic drinks from the United Kingdom...

Of course, the necessity to go to work somewhat limited the workers’ consumption of alcohol. Nevertheless, drunkenness among them far outstripped anything I have ever seen, before or since. I discovered that, when alcohol is effectively free of charge, a fifth of British construction workers will regularly go to bed so drunk that they are incontinent both of urine and feces. I remember one man who very rarely got as far as his bed at night: he fell asleep in the lavatory, where he was usually found the next morning. Half the men shook in the mornings and resorted to the hair of the dog to steady their hands before they drove their bulldozers and other heavy machines (which they frequently wrecked, at enormous expense to the British taxpayer); hangovers were universal. The men were either drunk or hung over for months on end.

Our soft-handedness on crime and drugs, is really an extreme hard-heartedness.

Saturday, June 28, 2008

The economy is like a rainforest

In the rainforest, there are places that are light or dark, hot or cool, high or low, wet or dry. In the economy, there are savers, borrowers, amateur and professional investors, crooks, marks, young bold, cautious old, workers, shirkers and berserkers.

So centralised economic policy is enormously difficult. An intervention that helps one part, may hurt another, and further action is implied. It's like the tablets for hypertension that give you gout, which means you need tablets for the gout, which are likely to harm the lining of your stomach. Some might say, throw the lot away and have a glass of sherry before bedtime.

Or, in rainforest terms, let each species find its niche and organise its own survival strategies.

But I don't think this is an argument for complete liberal laissez-faire. To extend the analogy, maybe it's better to prevent harm than to seek to do good; the forest guardians need to control the rubber and banana companies, the clear-cutting loggers and polluting miners.

Friday, June 27, 2008

Dow Jones - worse bubble than the FTSE?

Just out of interest, I thought I'd do the same trend-spotting exercise for the Dow Jones as I did yesterday for the FTSE, i.e. extrapolating the highs and lows in the late 80s and early 90s.

Just out of interest, I thought I'd do the same trend-spotting exercise for the Dow Jones as I did yesterday for the FTSE, i.e. extrapolating the highs and lows in the late 80s and early 90s.The results are very different. October 2007 saw the Dow's highest-ever peak, and today, after falling over 2,000 points from that point, it still stands about where it was in the tech bubble of December 2000 (see yellow line).

And my hi-lo wedge (red lines) suggest that the Dow has been seriously above trend for most of the last 11 years. Of course, you can draw lines however you like, but I'm trying to do approximately the same as for the FTSE and the implication is that the Dow "ought" to be between 7,000 - 10,000, centring around the 8,500 mark. This chimes with what Robert McHugh predicted last year (9,000). (If you draw the "high" line to connect the '87 and '94 peaks, the hi-lo lines converge towards 7,000!)

I wonder what's keeping it up?

Stockmarket crash - a golden opportunity

We could be approaching a once-in-a-generation Templeton opportunity, a financial fire-and-forget that could richly reward those who save very hard right now. Give the rifle another pull-through, hitch up your belt, and wait...

Thursday, June 26, 2008

The FTSE - semi-wild guesses about fair value

Using these parameters, the late 90s and early 00s were well above trend, whereas last year's highs only just peeped above the upper line and the current value is hovering a little above the centre of the hi-lo wedge.

The implications are that the next low, if it comes soon, shouldn't be worse than around 4,500, and by 2010 (when I'm guessing the tide will turn) the bracket would be in the 4,700 - 7,000 bracket, with a midpoint of c. 5,850.

Taking the market at close yesterday and extrapolating to that 5,850 midpoint, would imply a future return (ignoring dividends) over the next 16 months, of c. 2.5% p.a. - not nearly as good as cash, especially in an ISA. On the same assumptions, to achieve an ex-dividend return of 6% p.a. would require entry into the market at c. 5,400.

On this tentative line of reasoning, we should be looking for a re-entry opportunity somewhere in the 4,500 - 5,400 level, say 5,000. Shall we wait for the next shoe to drop?

Inflation vs deflation - the iTulip debate

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

How much of the crash is behind us?

The FTSE is closing somewhere around 5,666.10 today. It closed at 5,709.50 on 17 February 1998, which was the first time the market had breached today's level.

The FTSE is closing somewhere around 5,666.10 today. It closed at 5,709.50 on 17 February 1998, which was the first time the market had breached today's level. Tuesday, June 24, 2008

Littlejohn vs Toynbee

"... do you think about global warming when you're flying to your villa in Italy?"

A sought-after moment, I believe.

Investment in agriculture sparkles

Of course, the poor are being hit badly (not the poor here, who aren't really poor). Hendry argues that rising food prices will encourage more (and much-needed) investment in agriculture.

Monday, June 23, 2008

Taking a line for a walk

Timothy McMahon at FinTrend reckons we should be looking to buy into US stocks this summer, using the rate of return graph above.

Timothy McMahon at FinTrend reckons we should be looking to buy into US stocks this summer, using the rate of return graph above.How far should we heed the chartists? Like cardsharps fleecing marks on a sinking Mississippi paddlewheeler, are they better at short-term plays, but inattentive to catastrophe?

Does freedom from self-destruction need a nudge?

As it happens, this is the thesis of a new book, "Nudge", by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. It is critically reviewed by David Gordon here on the Mises website.

We are already being heavily nudged by our tax-greedy government and large commercial concerns, to gamble and drink away our wealth and future security. Surely there are ways in which we might diminish the temptation a little, to increase the possibility of rational, self-beneficial choice.

Comparisons are odious

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Plodding On

Of course, there's always foot patrols. Peter Hitchens has often pointed out the usefulness of walking the beat in preventing crime. It all went wrong in the Sixties. As J. B. Morton wrote in his fantasy-satirical "Beachcomber" column in the Daily Express at that time:

"A Dictionary For Today

...FLYING SQUAD: A special contingent of police whose business is to arrive at the scene of a crime shortly after the departure of all those connected with it."

So much for the pale blue Ford Anglia and the comical attempt to imitate American cops as portrayed in shows like "The Streets of San Francisco."

I had to trawl around to find what I remembered as the origin of the term "bobby on the beat", but here we are at last:

"A standard piece of police equipment from the 1830's to the 1880's was the rattle for raising the alarm, most operated like the standard football rattle, when twirled round it made a distinctive sound. In the 1880's the police began using a whistle in place of the rattle, early versions used the 'pea' type (still used by football referees) but in about 1910 the more familiar tubular 'air whistle' was invented. The whistle was carried inside the front of the tunic or jacket attached to a silver chain which was fastened to a button on the front of the tunic. When breast pockets appeared the whistle moved to the right hand pocket with a silver chain still attached to the jacket button. In practice the whistle was found to have limited range and a bobby calling for assistance would often beat his truncheon on the pavement to alert nearby colleagues. Police personal radios appeared in the 1970's and some forces had lost their whistles by the 1990's but other forces felt it was a part of the uniform and have retained it."

(Source)

And it worked. So instead of moving forward to the world of "1984" or re-creating the secret police of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, why don't we build on the notion of "Police Community Support Officers" (or "The Ankh-Morpork Watch" as my wife calls them) and revive the Watch as it was up until the early nineteenth century? The roots of our police force are in the citizens' right and duty to maintain order in their own communities. As motorised mobility for the peasantry declines, crime, its detection and punishment may well become localised again.

And a reduction in sophistication would be appropriate. The old police recruitment poster said "Can you Read? Can you write? Can you fight?" - not, "Can you gobble the punter's biscuits and swill his tea while expressing sympathy for his unfortunate experience and sharing his frustration at the powerlessness of the criminal justice system?"

Saturday, June 21, 2008

Handy-dandy, which is which?

The result in one case was declared unsatisfactory by the ruling party and an order given that the issue be readdressed within three months.

Robert Mugabe has yet to declare his candidacy for the Presidency of the European Parliament.

Grasping the nettle

I suppose it's a dangerous question to ask, but is assassination always morally wrong? Was the life of Nikolai Yezhov really worth the lives of 3 million of his victims?

This article justifies it in the context of Israeli national self-defence (no spittle-flecked anti-Semitic comments, please, the same arguments can be expressed using other contexts), but what if the enemy is within one's own society? For example, was Stauffenberg correct in his attempt to blow up Hitler, his leader?

I suppose this must lead to the question of whether right and wrong actions receive their due in another world, rather than this one, where villains appear much safer, live much longer, than the innocent. Mao, Stalin, Pol Pot, Idi Amin...

Why has Bill Gates stepped off now?

What I've read about business moghuls suggests that, however rich, they never want to give up. They can always try to get bigger and outdo, or do in, a business rival. Robert Maxwell's downfall was his obsessive competition with Rupert Murdoch, which got down to the personal. For example, learning that Murdoch had flown to New York for a business dinner at a swanky restaurant, Maxwell immediately got on Concorde and shot across the Atlantic, so he could be at a neighbouring table.

And these people will compete in the smallest way. I read an article which said in passing that while his chauffeur-driven car was waiting at a red light, Maxwell saw next to him a very nice sports car (possibly a Ferrari). He leaned out of his window and helpfully informed the neighbouring driver that his rear tyre was flat, so that as the man glanced back, Maxwell's car could be first through the intersection when the lights changed.

So why is Gates, such a fierce competitor that his employees refer to themselves as "Microserfs", "retiring" at 52? Is it because he is smart enough to know when his business has peaked, and seeing a rival in Google (and a challenge from freeware) that he can't beat (despite his firm's attempt to purchase Yahoo!), he's withdrawn before defeat is clear? In which case, what are the implications for investors in Microsoft?