*** FUTURE POSTS WILL ALSO APPEAR AT 'NOW AND NEXT' : https://rolfnorfolk.substack.com

Saturday, March 08, 2008

Survivalism

I sent a circular to my clients in the late 90s, urging them to take out redundancy insurance, because I thought the coming stockmarket crash would be followed by recession; but of course I didn't anticipate that the government would use monetary inflation to defer the reckoning (and, I now fear, make it worse). Articles like Coffey's are straws in the wind, I think.

Monday, February 25, 2008

Place your bets

To me, decoupling seems the least likely at this stage; I don't feel the rest of the world has yet built up demand sufficient to be unaffected by the loss of the American consumer. But what do I know.

I'm guessing the first scenario for a while, followed by the third when governments panic.

Thursday, February 14, 2008

A secular bear market in housing?

Here's some reasons, some having a longer-term effect than others:

- house prices are now a very high multiple of earnings, choking the first-time buyer market.

- presently, there is increasing economic pessimism, which will further inhibit buyers.

- the mortgage burden now lies in the amount of capital to be repaid, rather than the interest rate; that's much harder to get out of, and will prolong the coming economic depression, either through the enduring impact on disposable income, or through the destruction of money by mortgage defaults on negative-equity property - and as valuations fall, there will be more and more of the latter.

- fairly low current interest rates allow little room to drop rates further to support affordability - and at worst, rate drops could sucker even more people into taking on monster mortgage debt. But interest rate reductions are unlikely to benefit borrowers anyway. The banks have survived for centuries on the fact that while valuations are variable, debt is fixed. They got silly with sub-prime, but by George they will remain determined to get all they can of their capital back, and preserve its value. The people who create money literally out of nothing - a mere account-ledger entry - are now tightening lending criteria and will continue to press for high interest rates; for now, they will content themselves with not fully passing on central bank rate cuts, so improving the differential for themselves, as compensation for their risk.

- food and fuel costs are rising, and given declining resources (including less quality arable land annually), a growing world population and the relative enrichment of developing countries, demand will continue to soar, cutting into what's left of disposable income.

- our economy is losing manufacturing capacity and steadily turning towards the service sector, where wages are generally lower.

- the demographics of an ageing population mean that there will be proportionately fewer in employment, and taxation in its broadest sense will increase, even if benefits are marginally reduced.

- the growing financial burden on workers will further depress the birth rate, which in turn will exacerbate the demographic problem.

A market goes up when more people want to buy, than those that want to sell. Well, all of these first time home buyers have no spare cash for the Stock Market. The Baby Boomers, sometime in the future are going to want to sell. The question arises, "Sell to Whom?"

Returning to houses, there are still those who think valuations will continue to be supported by the tacit encouragement of economic migration to the UK.

Now, although this helps keep down wage rates at the lower end (where is the Socialist compassion in that?), the government is pledging the future for a benefit which is merely temporary, if it exists at all. Once an incoming worker has a spouse and several children, how much does he/she need to earn to pay for the social benefits consumed now and to come later? State education alone runs at around £6,000 ($12,000) per annum per child.

And then there's the cost of all the benefits for the indiginous worker on low pay, or simply unemployed and becoming steadily less employable as time passes. And his/her children, learning their world-view in a family where there is no apparent connection between money and work. The government makes get-tough noises, but in a recessionary economy, I don't think victimising such people for the benefit of newspaper headlines will be any use. I seem to recall (unless it was an Alan Coren spoof) that in the 70s, Idi Amin made unemployment illegal in Uganda; not a model to follow.

So to me, allowing open-door economic migration to benefit the GDP and hold up house prices doesn't work in theory, let alone in practice.

Besides, I maintain that in the UK, we don't have a housing shortage: we have a housing misallocation. There must be very many elderly rattling around alone in houses too large and expensive for them to maintain properly. This book says that as long ago as 1981, some 600,000 single elderly in owner-occupied UK property had five or more rooms; the ONS says that in 2004, some 7 million people were living alone in Great Britain. Then there's what must be the much larger number of people who live in twos and threes in houses intended for fours and fives. Before we build another million houses on flood-plains, let's re-visit the concept of need.

Maybe we'll see the return of Roger the lodger - if he's had a CRB check, of course.

Would I buy a second home now? No. Would I sell the one I live in? I'd certainly think about it - in fact, have been considering that for some years.

Sunday, February 03, 2008

Why equities should go down

Vitaliy Katsenelson explains that the current average price-earnings ratio may seem cheap, but that's because recent profit margins have been well above the 8.5% trend. Even allowing for a shift since 1980 away from industry towards the higher-margin service sector, the present 11.9% profit margin should be seen against a longer-term background figure of around 8.9 - 9.2%, which if current p/e ratios continue would imply a downward stock price correction of 22 -25%.

This chimes with Robert McHugh's "Dow 9,000" prediction from last July. And in many fields it's usual for overshoot to occur in the process of regression to a mean, so if it holds true in this case we could see even deeper temporary lows.

Day traders, be warned: this piste is a Black Run.

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Meow boing splat

People speak of the crash of 1929, but it took much longer for the crisis to work through and there were lots of opportunities for investors to step off with smaller losses. There were also plenty of traps for those who thought it was time to buy back in.

Here's a chart (source) of the process:

As they say, history doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes. Today's central banks are acutely aware of this past history and do not wish to be remembered for making the same mistake, i.e. worsening the situation by deliberately contracting the money supply.

However, Denninger and others think we can't stop this contraction anyway, once the credit bubble has been pricked, and attempts to reflate will merely devalue the currency while failing to stimulate the real economy.

Saturday, January 05, 2008

Bitter medicine

... the present crisis is already more serious than any that has occurred before in modern times.

... Our projections, taken literally, imply three successive quarters of negative real GDP growth in 2008. Spending in excess of income returns to negative territory, reaching -1.6 percent of GDP in the last quarter of 2012—a value that is very close to its “prebubble” historical average.

... while the rate of growth in GDP may recover to something like its long-term average, all our simulations show that the level of GDP in the next two years or more remains well below that of

productive capacity.

... We conclude that at some stage there will have to be a relaxation of fiscal policy large enough to add perhaps 2 percent of GDP to the budget deficit.Moreover, should the slowdown in the economy over the next two to three years come to seem intolerable, we would support a relaxation having the same scale, and perhaps duration, as that which occurred around 2001.

Our projections suggest the exciting, if still rather remote, possibility that, once the forthcoming financial turmoil has been worked through, the United States could be set on a path of balanced growth combined with full employment.

Unemployment B-L-S---

Karl Denninger reports that the US unemployment rate has hit 5%. He thinks - and it's certainly plausible - that we're already in a recession. Especially if Rob Kirby is right, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is lying about the scale of job losses in the financial industry.

Friday, January 04, 2008

Dead Cat Splat

His view: housing is woeful, emerging markets look as though they may be topping-out, the Ted Spread is signalling insolvency fears, the 10-year bond rate augurs slowing growth; so cash is king.

Little boxes, revisited

I think it's in "Jane Eyre": a teacher who wishes to instil piety into a little boy, asks him whether he'd rather have a biscuit or a blessing. When he answers, a blessing, he gets two biscuits.

When recession empties the the biscuit barrel, maybe we'll get authentic leadership.

UPDATE

My beloved recalled it better, and so I've found the quote on the Net:

...I have a little boy, younger than you, who knows six Psalms by heart; and when you ask him which he would rather have, a ginger-bread nut to eat, or a verse of a Psalm to learn, he says: "Oh, the verse of a Psalm! Angels sing Psalms," says he. "I wish to be an angel here below." He then gets two nuts in recompense for his infant piety.’

We need recession, to avert total disaster

It seems that we must wish our own countries a spell of hard times, in order to stimulate the changes that will defend us from permanent ruin.

Thursday, January 03, 2008

Mirror, mirror

Few are brave enough to come out and declare the start of a bear market; but the watchword is "proceed with caution".

Wednesday, January 02, 2008

Consequences

Sunday, December 30, 2007

Recession QED

He says the media is not reporting the truth. I tend to agree: I now throw away the Sunday football and financial supplements at the same time. If you want to know what's really happening, he says, watch what is going on at the banks, the Federal Reserve and Goldman Sachs, all of whom are battening the hatches, while CNBS (also castigated by Jim Willie) plays a cheerful tune to the proles.

I've written before how in 1999, as a financial adviser, I sat through a presentation from a leading UK investment house about tech stocks, which were supposedly about to start a second and bigger boom. I suspected then, and even more so now, that they were looking for the fabled "bigger fool" to offload their more favoured clients' holdings. Denninger intimates the same:

Are these shows, newspapers, and others reporters on the financial markets, entertainers, or worse, puppets of those who know and who need someone – anyone – to unload their shares to before the markets take a huge plunge, lest they get stuck with them?

Then he gives his predictions - which are grim, but not apocalyptic. It's the fools who will get roasted, not everybody. (By the way, Denninger is another Kondratieff cycle follower.)

What to hold, in his opinion? Cash, definitely; anything else, check the soundness of the deposit-taker. If you want to gamble on hyperinflation, he thinks call options on the stockmarket index are likely to yield more than gains on gold, even if the gold bugs are right.

This is where I thought we were in 1999. Thanks to criminally reckless credit expansion in the interim, we're still there, only the results may be worse than I feared then.

Oh, and he thinks the dollar will recover to some extent, because the rest of the world is going to get it just as bad, and probably worse. (Interesting that the pound is now back under $2.)

Friday, December 28, 2007

Desperate hope

However, many have already pointed out that (a) lending criteria are tightening and (b) not all of the interest rate cut is being passed on to the borrower. So lenders are trying to reduce their exposure and are also being paid more for the risk they have already assumed. And we see from this Christmas shopping season that (c) the consumer is becoming more reluctant to spend.

That's not to say that we won't get inflation (in some sectors, not housing), since falling interest rates tend to depreciate the currencies of debtor countries relative to their cash-rich trading partners. On the other hand, the latter will continue trying to hold down their currencies, in an attempt to keep the show on the road - the show being the osmosis of wealth from the lazy, spendthrift West to the hard-working, hard-saving developing world.

We're going to be buying less, but I don't know how fast the Eastern co-prosperity sphere will take up the slack. In his book "The Dollar Crisis", Richard Duncan argues for a worldwide minimum wage to stimulate demand; but maybe events have overtaken him. Certainly, China aims to expand its middle class, rapidly.

But there's another way for China to stave off depression while waiting for the sun to rise in the East. According to James Kynge, manufacturing and transportation costs account for only about 15% of the end-price of Chinese exports to the US. Some of the expanding Chinese middle class will surely go into advertising, marketing, sales, distribution and finance. As China develops its own version of Wal-Mart, Omnicom and banking, credit card and financing operations, it'll own more of the total profit in the supply chain - some of which it can sacrifice to retain market share. And they're motivated to do so by the fact that domestic consumption yields very little profit for their companies: the money's in exports. The longer this game goes on, the more the decline of capital and skilled labour at our end.

So let's worry about the effects at home first. Yes, for investors inflation may be a worry, but perhaps they should extend their concern to include the stability of the society in which they live, as unemployment and insolvency stalk through the West. The issues are no longer financial, but political and social.

And we'd better hope that we don't go for the wrong solutions. Daughty quotes Ambrose Evans-Pritchard's 12 December article in The Daily Telegraph, which concludes (amazingly), "... it may now take a strong draught of socialism to save the Western democracies." I do not think Mr Evans-Pritchard is very old. Or maybe he's just saying that to bug the squares, an expression I'll wager he's too young to remember.

Thursday, December 27, 2007

Defensive investing

I've never understood why the stockmarket seems serenely unrelated to the dire state of the economy. Supposedly the market "looks ahead" around a year, but it can't be seeing what I'm looking at.

Anyhow, Panzner reproduces Dan Dorfman's article in the New York Sun, which reviews what's happened to the market in past recessions and gives tips on strong defensive areas - booze, cigs and "household products". I can understand that, too - or the first two, at least.

Thursday, December 20, 2007

Hark what discord follows

What is inflation, anyway? Ronald Cooke looks at the damned lies and self-serving statistics that underpin the official Consumer Price Index.

Jim Patterson reads the stockmarket runes and concludes:

Sub-Prime issues have been discounted. With overall market returns compressed the downside is limited. We expect a better market in the weeks and months ahead.

In his slightly starchy prose, The Contrarian Investor agrees with Patterson, up to a point, but also gives a serious warning:

1. In today’s market, the probability of the market going up is higher than the probability of it coming down. Hence, it is rightly called a bull market.

2. But should it come down (which is unlikely), it can collapse at extremely great speed and magnitude.

Hence, the stronger and longer this uptrend continues, the greater in magnitude and speed (as in volatility, not timing) the Great Crash III will be. Hence, the coming Great Crash III is a Black Swan event—an improbable but colossal impact event.

The importance of a particular event is the likelihood of it multiplied by its consequences. Black Swan events are events that are (1) highly unlikely and (2) colossal impact/consequences. One common mistake investors (and many professionals) make is to look at the former and forget about the latter i.e. ignore highly unlikely but impactful events.

Therefore, when contrarians are preparing for a crash, it does not necessary mean that they are predicting doom and gloom. Rather, they see the vulnerability of Black Swans and prepare for them.

Saturday, December 01, 2007

The Angriest Guy In Economics

Karl Denninger, on the other hand, is very emphatic that our economic woes are no laughing matter. Here he calls for all the "off-book" items to be included in lenders' accounts, and if that bankrupts them, so be it: a cleansing of the financial system, condign punishment for the perpetrators and a warning to others. This is similar to Marc Faber's position: he says the crisis should be allowed to "burn through and take out some of the players". Gritty.

And concrete. Denninger supplies a photo of a customer-empty store at 6 p.m. on a Sunday evening, to underscore his point.

Now that's something we can put to the test - look at the shops in your area and work out how crowded you'd normally expect them to be at the beginning of December.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Michael Panzner on Michael Panzner

Predicting tough times ahead, Michael Panzner, author of Financial Armageddon, recommends that investors buy shares of companies that sell stuff that people need to buy no matter what's going on with the economy. Companies that sell soft drinks, tobacco, prescription drugs and toilet paper, for example.

Investors, he says, should play it safe, loading up on defensive stocks, socking away more cash and moving toward the safety of U.S. Treasury notes and bonds.

Sunday, November 25, 2007

Long or short crisis? Inflation or deflation?

An interesting post from Michael Panzner, commenting on the views of derivatives expert Satyajit Das. The latter thinks we're in for a 70s-style inflationary grind, whereas Mr Panzner leans towards a 30s-style deflation.

I am reminded of Borges' short story, "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote". In this, a modern author attempts to re-produce the 16th century novel "Don Quixote" by Cervantes: not copying - writing it again exactly, but as though for the first time ever. Since Menard is writing in a different period of history, the same words have quite different meanings, implications and associations. To pen the identical lines today, spontaneously, would involve a monstrous effort. So Borges' tale is a wonderful parable about the near-impossibility of our truly understanding the mindset of the past, and how history can never be quite repeated, because the present includes a knowledge of the past that it takes for its model.

For those reasons, we'll never have the Thirties again, or the Seventies; but we might have a retro revival. And the differences may be as significant as the similarities.

Ken Kesey's bus (named "Furthur"), and part of the commercialised modern follow-up

Ken Kesey's bus (named "Furthur"), and part of the commercialised modern follow-upSaturday, November 24, 2007

Why the sea is salt, and why we are drowning in cash

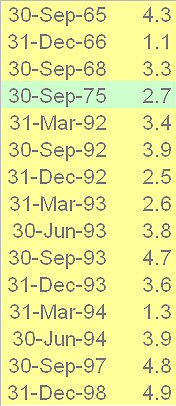

As you see, mostly it was the nineties, with one instance in 1975 and three times in the sixties. The average rate for the whole series up to December 2006 is 13.47%. So the hand-mill never stops grinding.

As you see, mostly it was the nineties, with one instance in 1975 and three times in the sixties. The average rate for the whole series up to December 2006 is 13.47%. So the hand-mill never stops grinding.

But should it? Wikipedia gives an account of recession and the Great American Depression, and notes that during the latter period the money supply contracted by a third. Great for money-holders, bad for the economy and jobs.

This page points out that we tend (wrongly) to think of a period of economic slowdown as a recession, and says that technically, recession is defined as two successive quarters of negative economic growth. By that measure, we haven't had a recession in the UK (unlike Germany) for about 15 years - here's a graph of the last few years (source):

Mind you, looking at Wikipedia's Tobin's Q graph, the median market valuation since 1900 seems to be something like only 70% of the worth of a company's assets. Can that be right? Or should we take the short-sighted view of some accountants and sell off everything that might show a quick profit?

Nevertheless, it still feels to me (yes, "finance with feeling", I'm afraid) as though the markets are over-high, even after taking account of the effects of monetary inflation on the price of shares. And debt has mounted up so far that a cutback by consumers could be what finally makes the economy turn down. Not just American consumers: here is a Daily Telegraph article from August 24th, stating that for the first time, personal borrowing in the UK has exceeded GDP.

The big question, asked so often now, is whether determined grinding-out of money and credit can stave off a vicious contraction like that of the Great Depression. Many commentators point out that although interest rates are declining again, the actual interest charged to the public is not falling - lenders are using the difference to cover what they perceive as increased risk. Maybe further interest rate cuts will be used in the same way and keep the lenders willing to finance the status quo.

Some might say that this perpetuates the financial irresponsibility of governments and consumers, but sometimes it's better to defer the "proper sorting-out" demanded by economic purists and zealots. History suggests it: in the 16th century, if Elizabeth I had listened to one party or another in Parliament, we'd have thrown in our lot with either France or Spain - and been drawn into a major war with the other. We sidestepped the worst effects of the Thirty Years' War, and even benefited from an influx of skilled workers fleeing the chaos on the Continent. If only we could have prevented the clash of authoritarians and rebellious Puritans for long enough, maybe we'd have avoided the Civil War, too.

So perhaps we shouldn't be quite so unyielding in our criticisms of central bankers who try to fudge their - and our - way out of total disaster.

Terry Gilliam's take on the old tale

Terry Gilliam's take on the old tale