Thursday, January 03, 2013

Nick Drew: Solar fad a waste of money

Energy expert and journalist Nick Drew has written a new piece for The Energy Page on cost-effective ways to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Turns out that the fashion for roof-mounted solar panels is just about the worst possible option - read the full story here.

Nick is a regular contributor to the Capitalists@Work blog.

************

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Solar Power is Daylight Robbery

The UK government is very fond of claiming that its decarbonisation policy is being delivered at least cost to UK citizens. Irrespective of whether one supports the policy goal, one would at least like to believe them on the cost.

Sadly, their claim is a blatant falsehood; and we can see why this is by utilizing the government's own methodologies.

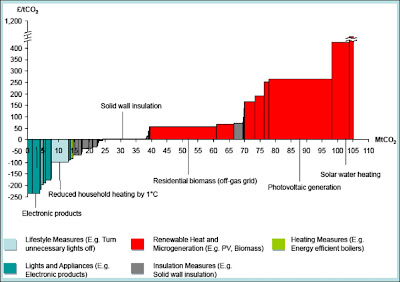

A very standard way of presenting the cost-effectiveness of measures that can reduce CO2 emissions is the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) and we will look at some examples below. The basic concept is simple: for each measure, calculate the cost per unit of CO2 emissions reduced, and rank them from cheapest to most expensive on a bar-chart. If we pick (e.g.) a particular market segment, we can additionally plot the total absolute potential for CO2 abatement each measure can deliver in that sector (e.g. in tonnes), by making the width of each bar correspond to the amount.

Having ranked them thus, for a given target amount of reductions we can directly read off the cost of the most expensive measure required to achieve the target. And why would anyone institute measures that cost more than absolutely necessary ? Surely, they would exhaust the potential of the cheapest measures first, before proceeding to the more expensive.

Before looking at UK examples, it is interesting to note that in every MACC example one ever sees, the cheapest abatement measures are in fact profitable - that is, they pay for themselves - in some cases, handsomely so: their 'cost' is not just cheap, it is negative. (We will consider what this means in policy terms another time.) Our first example shows this aspect clearly: it comes from DECC and is the MACC of the total potential abatement identified in the UK 'non-traded' sector (the part of the economy not subject to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme), for the period 2023–27.

As can be seen, at the left-hand side there is around 90 MtCO2e abatement potential that pays for itself. We should only need to start paying for abatement if the target was in excess of that amount. The weighted average of the cost (by a complex calculation) is £43 per tonne, which coincides with an abatement potential of around 130 Mt - well over half the total. Even the most expensive measures plotted come in at under £250 per tonne.

This, then, is a baseline of sorts, and certainly gives some background perspective for considering the next chart, which is the detailed MACC for abatement potential in the UK residential sector through to 2020.

Note that solar power (PV generation) is well to the right of the curve, with a cost that towers over most of the measures available. (Solar water-heating is even worse.) Secondly, at £265 per tonne it is more expensive than any of the measures from the previous MACC.

A very obvious conclusion must surely be that solar power should not be receiving public money (via whatever mechanism) until the vastly greater potential that is available at very much less cost has been comprehensively exploited. Needless to say, the opposite is the case: residential solar power installations are heavily subsidized via our electricity bills, while huge amounts of cheaper - much cheaper - abatement potential lies dormant.

No end of sophistry is offered to defend this state of affairs. Costs of PV are falling all the time; many jobs have been created (mostly in China, of course); we need to create a level playing-field for all technologies (whatever that means). And there are all manner of nuances relating to the interpretation of MACCs - as DECC is keen to tell us (Box B5 here).

No amount of ratiocination, however, can deflect the accusation that subsidizing solar PV in the UK is indefensible from a cost perspective. And in straightened times, costs matter.

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Sadly, their claim is a blatant falsehood; and we can see why this is by utilizing the government's own methodologies.

A very standard way of presenting the cost-effectiveness of measures that can reduce CO2 emissions is the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) and we will look at some examples below. The basic concept is simple: for each measure, calculate the cost per unit of CO2 emissions reduced, and rank them from cheapest to most expensive on a bar-chart. If we pick (e.g.) a particular market segment, we can additionally plot the total absolute potential for CO2 abatement each measure can deliver in that sector (e.g. in tonnes), by making the width of each bar correspond to the amount.

Having ranked them thus, for a given target amount of reductions we can directly read off the cost of the most expensive measure required to achieve the target. And why would anyone institute measures that cost more than absolutely necessary ? Surely, they would exhaust the potential of the cheapest measures first, before proceeding to the more expensive.

Before looking at UK examples, it is interesting to note that in every MACC example one ever sees, the cheapest abatement measures are in fact profitable - that is, they pay for themselves - in some cases, handsomely so: their 'cost' is not just cheap, it is negative. (We will consider what this means in policy terms another time.) Our first example shows this aspect clearly: it comes from DECC and is the MACC of the total potential abatement identified in the UK 'non-traded' sector (the part of the economy not subject to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme), for the period 2023–27.

|

| Source: DECC |

This, then, is a baseline of sorts, and certainly gives some background perspective for considering the next chart, which is the detailed MACC for abatement potential in the UK residential sector through to 2020.

|

| Source: Committee on Climate Change |

A very obvious conclusion must surely be that solar power should not be receiving public money (via whatever mechanism) until the vastly greater potential that is available at very much less cost has been comprehensively exploited. Needless to say, the opposite is the case: residential solar power installations are heavily subsidized via our electricity bills, while huge amounts of cheaper - much cheaper - abatement potential lies dormant.

No end of sophistry is offered to defend this state of affairs. Costs of PV are falling all the time; many jobs have been created (mostly in China, of course); we need to create a level playing-field for all technologies (whatever that means). And there are all manner of nuances relating to the interpretation of MACCs - as DECC is keen to tell us (Box B5 here).

No amount of ratiocination, however, can deflect the accusation that subsidizing solar PV in the UK is indefensible from a cost perspective. And in straightened times, costs matter.

* * * * *

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Wednesday, January 02, 2013

Does the stockmarket correlate with energy usage?

I've suggested recently that not only does modern money fail to act as a store of value, it is failing as a unit of account because of central bank/government interference in its quantity and distribution. It's an elastic ruler and its unreliable measurements are a factor in unsatisfactory decisions (misallocation of resources, as the monetarists say). So we look for alternative ways to assess relative advantage.

One more scientific-seeming (but complex) measure is energy. Professor Charles Hall adapted the notion of energy return on (energy) investment (EROI, or EROEI) from the biological sphere (where he began his studies) to human social-economic systems. This appears to be a promising method for analysing different forms of commercial energy production.

However, the entry linked above goes on to claim a correlation between the stockmarket and energy usage:

... a century's market and energy data shows that whenever the Dow Jones Industrial Average spikes faster than US energy consumption, it crashes: 1929, 1970s, the dot.com bubble, and now with the mortgage collapse.

I'm not so sure, and I've had a look for the evidence. So far, I've come across a study by the US Energy Information Administration of oil futures vs stock and other indices, and over the admittedly fairly short period covered, the correlation with the Dow is not uniformly high, though it has increased since the Credit Crunch:

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

One more scientific-seeming (but complex) measure is energy. Professor Charles Hall adapted the notion of energy return on (energy) investment (EROI, or EROEI) from the biological sphere (where he began his studies) to human social-economic systems. This appears to be a promising method for analysing different forms of commercial energy production.

However, the entry linked above goes on to claim a correlation between the stockmarket and energy usage:

... a century's market and energy data shows that whenever the Dow Jones Industrial Average spikes faster than US energy consumption, it crashes: 1929, 1970s, the dot.com bubble, and now with the mortgage collapse.

I'm not so sure, and I've had a look for the evidence. So far, I've come across a study by the US Energy Information Administration of oil futures vs stock and other indices, and over the admittedly fairly short period covered, the correlation with the Dow is not uniformly high, though it has increased since the Credit Crunch:

Granted, energy usage and energy prices are not necessarily tightly bound together, but does the above tend to disprove or prove the assertion that the Dow cannot long outrun energy use?

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Monday, December 31, 2012

Proud to be a bear

The Yorkshire vet "James Herriot" wrote of a rich farmer whose principle was, "When all the world goes one way, I go t'other."

Barry Ritholtz publishes a report by James Bianco saying that the Investor's Intelligence survey of investment newsletters shows bearishness at its lowest since 1963.

When nearly everyone agrees, nearly everyone's wrong. The system hasn't been fixed yet and we haven't yet had to face up to the full cost of the consequences. I'm not an active trader - how can you beat the City gunslingers? - so instead of trying to predict the waves I look for the tide.

Until the British Government withdrew Index-Linked Savings Certificates, I'd have settled for them, since I'm more interested in not losing than in making a killing. Now, and until money velocity levels out and QE leads to serious inflation, it's cash for me, plus, reluctantly at these prices, gold.

I agree with Mish:

_____________________

_____________________

Proud to be a 5%-er, then.

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Barry Ritholtz publishes a report by James Bianco saying that the Investor's Intelligence survey of investment newsletters shows bearishness at its lowest since 1963.

When nearly everyone agrees, nearly everyone's wrong. The system hasn't been fixed yet and we haven't yet had to face up to the full cost of the consequences. I'm not an active trader - how can you beat the City gunslingers? - so instead of trying to predict the waves I look for the tide.

Until the British Government withdrew Index-Linked Savings Certificates, I'd have settled for them, since I'm more interested in not losing than in making a killing. Now, and until money velocity levels out and QE leads to serious inflation, it's cash for me, plus, reluctantly at these prices, gold.

I agree with Mish:

_____________________

- Gold has been sinking, as it should, if Congress is fiscally prudent.

- Government Should be Prudent

- Government Won't Be Prudent

_____________________

Proud to be a 5%-er, then.

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Why fracking - and other energy alternatives - won't save us completely

The discovery of large reserves of shale oil and gas has raised hopes that our economies may be rescued by a new energy bonanza. But this is not a rerun of the 1970s North Sea Oil boom that gave the UK economic relief for decades afterwards.

Attention is focused on the quantities of reserves, but the missing factor in the analysis is what it costs to exploit the energy source. What we should be looking at is "net energy profit", also known as the "energy profit ratio" or "energy return on investment (EROI)". The "profit" is accounted for not in dollars but in energy - what is put in, versus what is made available to the end user.

The table below is taken from an August 2010 article by Roger Blanchard of Lake Superior State University. It shows that the energy profit from shale oil is a mere 10% of what was obtainable from 1970s conventional oilfield production.

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Attention is focused on the quantities of reserves, but the missing factor in the analysis is what it costs to exploit the energy source. What we should be looking at is "net energy profit", also known as the "energy profit ratio" or "energy return on investment (EROI)". The "profit" is accounted for not in dollars but in energy - what is put in, versus what is made available to the end user.

The table below is taken from an August 2010 article by Roger Blanchard of Lake Superior State University. It shows that the energy profit from shale oil is a mere 10% of what was obtainable from 1970s conventional oilfield production.

Other energy sources are even worse. For example, corn ethanol barely covers its energy costs and is controversial because it harms the poor: a May 2012 study concludes that the price of corn has tripled in Mexico because of this additional demand and associated financial speculation.

Wikipedia offers this EROI comparison of energy sources:

Corn ethanol is even worse than solar, and that's saying something.

Of the renewables, wind turbines look promising, though they are also stigmatised by some as noisy, unsightly bird-chopping machines. And the estimated EROI on them varies startlingly, according to this graph from a 2007 article in "Encyclopedia of the Earth" (updated 2011):

Accounting for every scrap of energy in the process - from the production of equipment to its ultimate decommissioning - must be hideously complex, leaving the debate open to skewing by a variety of competing commercial interests and pressure groups (including, no doubt, the publishers of the above).

But accounting in financial terms is also biased by subsidies and permissions granted at the whim of governments swayed by industry lobbyists or trying to earn political credit with environmentally-minded voters. Money has already lost one of its three functions - as a store of value - and thanks to official interference in its quantity and distribution, is now rapidly losing another - its value as a unit of account, to inform decisions. Otherwise we would be unlikely to see so many British homes festooned with solar panels - an enthusiasm that has waned dramatically since the subsidy was cut this year.

Renewables will only go a small way towards replacing fossil and nuclear fuels, and shale fuels cannot promise "business as usual" in the meantime. Energy is not going to run out soon, but it will become more expensive, and our focus in the next few decades should be on restructuring the way we live. We didn't do that when North Sea oil was gushing. Shale is pricey and will be attended by inconvenience and controversy, but it may be our last chance to adapt without even more catastrophic disruption to normal life.

Nothing here should be taken as personal advice, financial or otherwise. No liability is accepted for third-party content, whether incorporated in or linked to this blog; or for unintentional error and inaccuracy. The blog author may have, or intend to change, a personal position in any stock or other kind of investment mentioned.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)