Whole new industries are waking up to a New China, with a middle class...and millions of rich people too... We spoke to a young man here who believes that the key to making money in large US companies actually lies in Asia.

"US companies aren't going to make much money by selling more product to Americans. Americans don't have any money... A company with a good product - especially a good brand - can make a lot of money now by doing two things. One is lowering its costs by outsourcing labour to Asia...not just manufacturing, but even high-level things like design, research, marketing, legal work. The other thing it has to do is to sell its products to this huge rising market of the Asian middle class.

"If it does these two things, it will have lower costs and higher revenues. If it doesn't do these two things, it will be stuck with high costs...and a stagnant market - at best. Actually, as the housing problem deepens in the United States, you'd expect domestic sales to fall."

He's probably right. While the average American will probably grow poorer - in both relative and absolute terms - many US companies will probably do quite well. Many already are.

I've suggested before now, that the white-collar people here are next in the firing line. Those mushrooming Third World (first-class) universities aren't just turning out engineering graduates. James Kynge pointed out that maybe 85% of the end-price of our Chinese imports is added on by sales and marketing. There's a strong incentive for developing Madison Avenue East. Not to mention Great Wall Street.

The good news for investors is that you may be able to make some money stock-picking the right Western companies, where access to shares is easier, accounts are not quite so dodgy, the government doesn't generally have its hand up the corporate puppet, and even governments have (to some degree) to obey the law and respect private property.

Returning to the gold-bubble question, Bill repeats the argument that gold is a haven in a storm, and mooring is getting cheaper:

There are times when the investing world becomes so dangerous that the most likely rate of return for the average investor will be negative. That is a good time to hold gold; your rate of return will almost certainly be better than actually investing! Gold is a hedge against the unknown... But like any insurance, it costs money. When you hold gold, you give up the yield you would otherwise get from stock dividends or bond coupons. Now that Bernanke has cut short-term rates, the cost of holding gold has gone down.

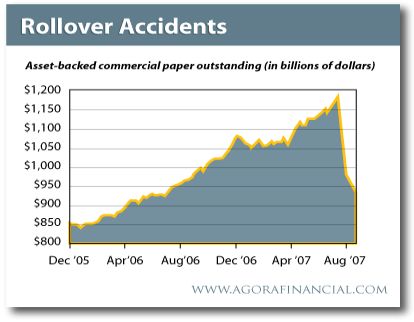

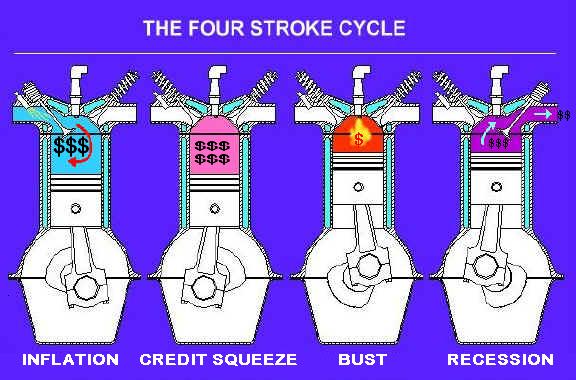

Is now the time to buy gold? The money supply in the United States is rising at a rate nearly five times the growth of the economy itself. The Fed, claiming that inflation is now under control, has just cut the price of credit to member banks by half a percentage point. The economic explorer has to rub his eyes and look twice; he can't quite believe it. How can inflation be under control when prices for key commodities - notably the keyest commodity, oil - are at record levels? He doesn't have an answer, but he can put two and two together. Whatever kind of 'flation' the Fed has been cooking up, we're going to get more of it. So put on your best bib and tucker, dear reader.