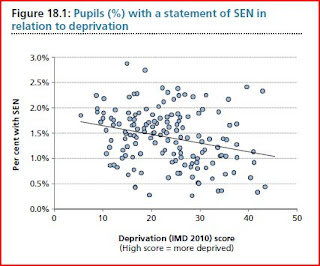

One might (perhaps) expect that less wealthy areas of England would have a higher proportion of children identified as having Special Educational Needs (SEN). Not so, according to this graph on page 103 of the NHS Atlas of Variation in Healthcare (November 2011 edition):

Using a measure called Indices of Multiple Deprivation and correlating it with the proportion of primary age children with a SEN Statement, it seems that children from poorer areas are less likely to be so diagnosed.

I don't think that's a true reflection of underlying need. There's loads of children with EBD (emotional and behavioural difficulties) and pace Mr Clegg the modern pattern of disrupted family structure really doesn't tend to help them. Perhaps schools that have more such children accept the situation as "normal"; or maybe their SENCOs (Special Educational Needs Coordinators) are simply overwhelmed. It's notable that primary age children are more likely to get excluded in Year 6, as the dreaded teacher-damning SATS exams draw near and the school finally decides that it can't afford to have a severely disruptive child in the group - was there really no such difficulty in the years before that?

But there are other kinds of need. Autism is an interesting case, and incidence of diagnosis is seemingly influenced by the social class of the family - an ASD (autistic spectrum diagnosis) expert in Birmingham LEA told us a year or two ago that the better-off quarters of Birmingham were yielding an ASD diagnosis rate some five times higher than in poorer areas. Perhaps it's because ASD doesn't carry the same potential stigma for the parent - it's genetic rather than a consequence of poor parenting skills - and perhaps also it's because it's a good way to attract extra attention and resources for your child (autism is a lifelong condition, unlike, er, "naughtiness").

Not that autism isn't real - I have taught autistic children all the way from mild cases down to the ones that can't or don't speak at all. But middle-class parents are (naturally) better at fighting their child's corner to get the diagnosis. And it strengthens their arm that the techniques and resources specifications in SEN statements are legally enforceable - such fun, as Miranda Hart's on-screen mum likes to say.

So in some ways the graph above is inadequate - it needs to be broken down into types of disability, and further into economic sub-divisions of the LEA (there is a world of difference between, say, Nechells and Hall Green). But even with the data aggregated in the way it is, there seem to be more questions to ask about inequalities in diagnosis and provision.

11 comments:

Somebody's done well to put a line through those results - on a purely visual estimation, I would say there is no correlation between the two variables.

Thanks for your comment, ReefKnot. I'm no statistician, so I can't say.

But the way the results are aggregated doesn't help, either. Too many apples, oranges and other produce in those bags.

Actually, if we're doing a visual assessment, it looks as though the divergence is greater as deprivation scores rise. Perhaps poorer areas get more uneven quality of special needs assessment?

The massive increase in SEN is a huge worry because there are many who don't need corralling in this way but the all-inclusive love everyone system which is the most intolerant thing in three decades insists that children are defined and corralled.

I don't know if we have more SEN children - we have more labelled as such.

That's one way to look at it, James, but I'd say that we are simply noticing more of what there was already. My mother-in-law was dyslexic but just got clumps on the side of the head for not reading properly.

And isn't loving everyone the core of your religious philosophy?

I'm with Reefknot here: what's the correlation in that diagram, negative but absurdly small. It proves nothing and suggests very little.

It is not at all surprising that diagnoses of various special "needs" are increasing - they bring with them increased funding, and one thing we know for sure is that if you want more of something, you subsidise it. This applies to "disabilities" just as much as it does to windfarms.

Neither is it in the least astonishing that middle-class areas report more autism: at the milder levels, autism - like ME - afflicts those who can afford to have it.

Hi, WY. I think it illustrates a couple of things:

1. Correlating with the Index of Multiple Deprivation is not as useful as, say, doing the same with Free School Meals.

2. Here as elsewhere, the middle class show themselves to be better at taking advantage of opportunities in the system. Among children with "Statements" of special needs, autism is the largest category, followed by moderate learning disability; and there is clear evidence that autism is more likely to be diagnosed for children from better-off families, although a Californian study shows that the poor are gradually catching up. Actual incidence of this condition appears to be around 0.4%. But it is a real condition, and so is ME.

I do believe that autism and ME are real - I was careful to qualify my cynicism with "at the milder levels" where I am not so sure.

Does anyone, though, have any idea why these two particular conditions - whatever they may be - are now quite commonplace and accepted, whereas forty years ago they were completely unknown? I struggle to believe it's ALL down to better diagnosis.

Sedentary lifestyles? Too many computers? The hygiene obsession? Unsuitable diets? Global warming?

Anyone?

Good question. With ASD I think it's always been there but either not noticed or explained away in other terms.

ME, no idea. But many of those who survived the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic also seemed de-energised, catatonic. Perhaps ME is a reaction by some individuals to some viruses? There's so many more of us now, and much more human intermingling in our industrial societies, and goods and food move around so much more, that maybe there's more likelihood of catching viruses?

I think I'd best disabuse Weekend Yachtsman of his cynical attitude to middle class autism. And just for the record, I'm speaking as someone "middle class" who has a son with mild Asperger's Syndrome, (on the Autistic Spectrum), and whose wife works as a Special Needs Coordinator, partly because of our experience with our son.

There are NO "opportunities" to take advantage of, whatsoever, unless the child has a severe disability - and in that case places at special schools are in far too short a supply. There is the stigma attached to being "Special", but no money at all.

Special Needs Departments are starved of funds, and at the less severe end there is simply no money whatsoever for more than perhaps an annual check on how the child is progressing.

There are many reasons for this, not just better diagnosis. One of them from what I can see as a "near observer" is the sheer number of recent immigrants making use of these services. Partially because if you are a citizen of an Eastern European EU country and you have a child with problems then it makes sense to move to a richer EU country with better developed social services - especially if there are extra benefits for the family. Another would be the levels of inbreeding amongst South Asian Moslems who have been marrying their cousins for generations and as a result have disability levels ten times those of the general population. It might not be politically correct to mention these aspects, but that doesn't change the facts.

Finally, the rise of autism is probably down to a couple of factors. The first is simply better diagnosis - the eccentric weirdo is now recognised as being Aspie. The other is the rise in "systematising" professions such as computing which has provided an outlet for these talents along with a greater opportunity for people with these tendencies to meet, marry and procreate. Silicon Valley is an autism hotspot and for that matter I am a computer programmer myself.

Thanks, Wildgoose, a most interesting comment. Your last squares with my brother's oft-repeated point about the value of (desperate need for) nerds and the mildly autistic in our modern technological societies.

Post a Comment