*** FUTURE POSTS WILL ALSO APPEAR AT 'NOW AND NEXT' : https://rolfnorfolk.substack.com

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Economics in the dark

In advanced economies, it's important for companies, banks and individuals to receive such information, too.

But nearly 40 years later, the USA needs to re-learn the lesson. The Federal Reserve ceased reporting M3 money supply data in 2006; accurate assessment of inflation is complicated by "hedonic adjustment" and periodic (and tendentious?) alteration of the types of item included in price surveys; the Bureau of Labor Statistics seasonally adjusts unemployment figures so that an increase can sometimes appear to be a decrease; nobody (not even the lenders) yet knows the full figures on bad loans and "Tier 3 assets"; it is not even clear how we should assess a nation's wealth (GDP per capita seems a misleading measure).

How can you navigate without up-to-date information? Even in the nineteenth century, Mississippi river pilots had to keep track of the river's changes, or risk getting stranded on new sandbars. And as John Mauldin reports, party political manoeuvering is stymying two appointments to the Federal Reserve's Board, at a time when the Fed most needs to concentrate on resolving the unfolding complex financial crisis.

Even given the right data, decision-making has become tougher. Increasing global interconnection and wealth transfer between nations means that normal cycles may be broken by epochal linear developments, so the past is now a very unsafe guide to the future.

We need clarity, direction and vision.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Can freedom be designed?

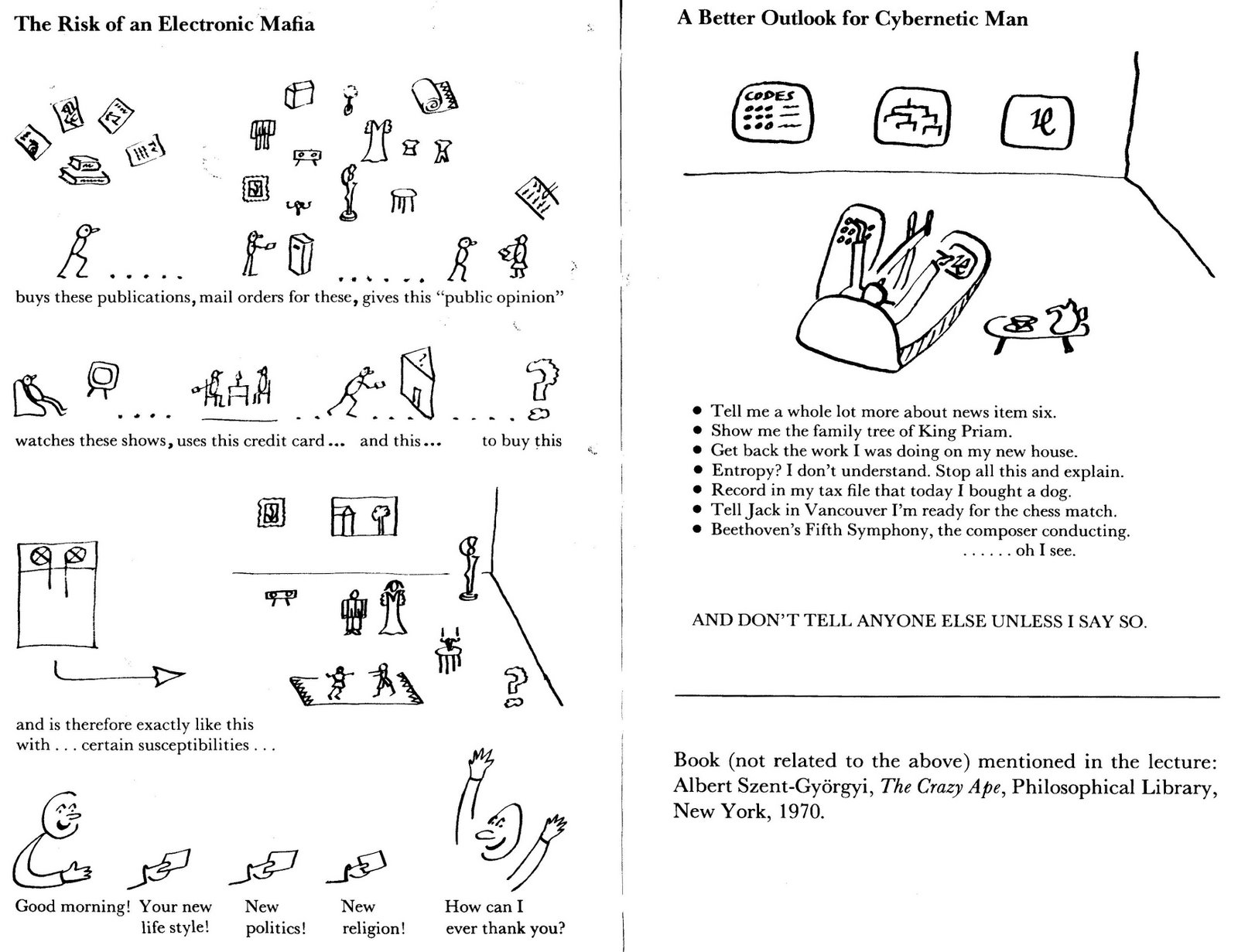

In the late 1970s, I read a book by Stafford Beer called "Designing Freedom". Unlike other management theory texts I've seen, it used cartoons and humour, though it also occasionally used language seemingly designed to cut out the layman - one gets the impression that business professors can be a sort of Glass Bead Game hermetic elite.

And I've just been trying to watch a lecture by him, recorded on video in 1974 and released on the internet by UMIST's archive (here). Maybe it's my computer, but the material is streaming in stits and farts; nevertheless, it's very interesting indeed.

Beer was invited to Chile to set up a system for the Allende government, to help manage the economy of a strangely-shaped and very diverse country. The project was never completed, since Allende was overthrown within a couple of years, but the ideas outlined in this video and the book I've mentioned were very far ahead of their time and probably somewhat ahead of ours, too.

At a time when computers were much less powerful than today, he was advocating their use to gather and crucially, filter, information in a way that allows decision-makers to make timely, well-informed (but crucially again, not over-informed) interventions. In the Chilean experiment, a system of telex machines across the country fed real-time data to a central (the only) computer, which then fed back decision-making alerts at every level from factory to government ministry.

Two things stand out for me:

1. You don't need all the information: you need to know of any significant change. (I have heard that toads only see likely prey if it moves, not when it is sitting still.)

2. You need relevant data fast, otherwise there is a danger that, owing to information time-lag, you will make exactly the wrong move. Beer said that this was a principal cause of the stop-go British economy. In today's context, maybe that's why the economy and the stockmarkets gyrate so wildly even now.

Beer emphatically denies that his system was intended to centralise power into a dictatorship, though in "Designing Freedom" he certainly sees its potential for tyranny. Instead, the model is a set of feedback systems akin to those that living creatures need to survive and to adapt to a changing environment.

Another point I've always remembered - and I think I must have seen it in another of his books, for I can't find it here - it that both resources and decision-making must be devolved, for maximum effectiveness. You give Department X a budget and a set of objectives, and let that department work out how best to use the resources to fulfil its brief. This is a lesson that the current micro-managing British regime has apparently never understood.

He was a real visionary - look at the contrasting pair of cartoons from the book, and remember that it was published 33 years ago. And buy it, as I have just done.

(By the way, my comments are not unduly influenced by the fact that he gave up most of his material possessions and moved to western Wales, devoting himself to art and poetry.)